This post first appeared in November 2024, but for those of you who missed it, I’m delighted to offer it again. Enjoy.

When asked about the earliest modern preservation movements in our country, most of us would have to do a bit of research, at the end of which, Charleston, South Carolina would emerge as the leading candidate. Indeed, The Preservation Society of Charleston claims the honor, proudly pointing to their founding in 1920 as a result of Susan Pringle Frost’s heroic efforts to save the Joseph Manigault house, circa 1802, which was set to be demolished. First named The Society For The Preservation Of Old Dwellings, the organization still survives today.

And as much as I can personally relate to and applaud Frost’s crusade, having founded a local preservation non-profit in my own small town in 2021 in order to save the oldest brick building in our midst, I am also happy to report that another small North Carolina town actually left the starting gate a full two years ahead of Susan Pringle Frost in Charleston.

Those of you who have followed the unfolding story of Hayes Farm in Edenton, NC for the past year already know that Hayes is but the latest chapter in a long history of preservation leadership that reaches all the way back to the year 1918.

That is the year when local residents became alarmed over the sale to the Brooklyn Museum of very important historic woodwork from Cupola House, circa 1756-1758. The sale caused such a stir that the citizens of Edenton decided to band together and form the Cupola House Association to ensure that nothing else of importance would slip through the town’s fingers.

The formation of that non-profit marks the birth of the modern preservation movement in the state, a movement that is still alive and well today. In fact, when it comes to preservation efforts, the people of Edenton, NC came to play and aim to win.

Today’s post takes a look at two recent developments that have, yet again, placed Edenton at the center of the preservation universe. In each case, they deal with important pieces of Edenton’s historic story.

As the work at Hayes Farm continued at full throttle this fall, news came of a very important auction being held at Brunk Auctions in Asheville, NC. Among the items being auctioned were significant artifacts that originally resided at Hayes, not the least of which was an extremely rare printed archetype copy of the United States Constitution which ended up selling for an eye-popping amount to an undisclosed buyer.

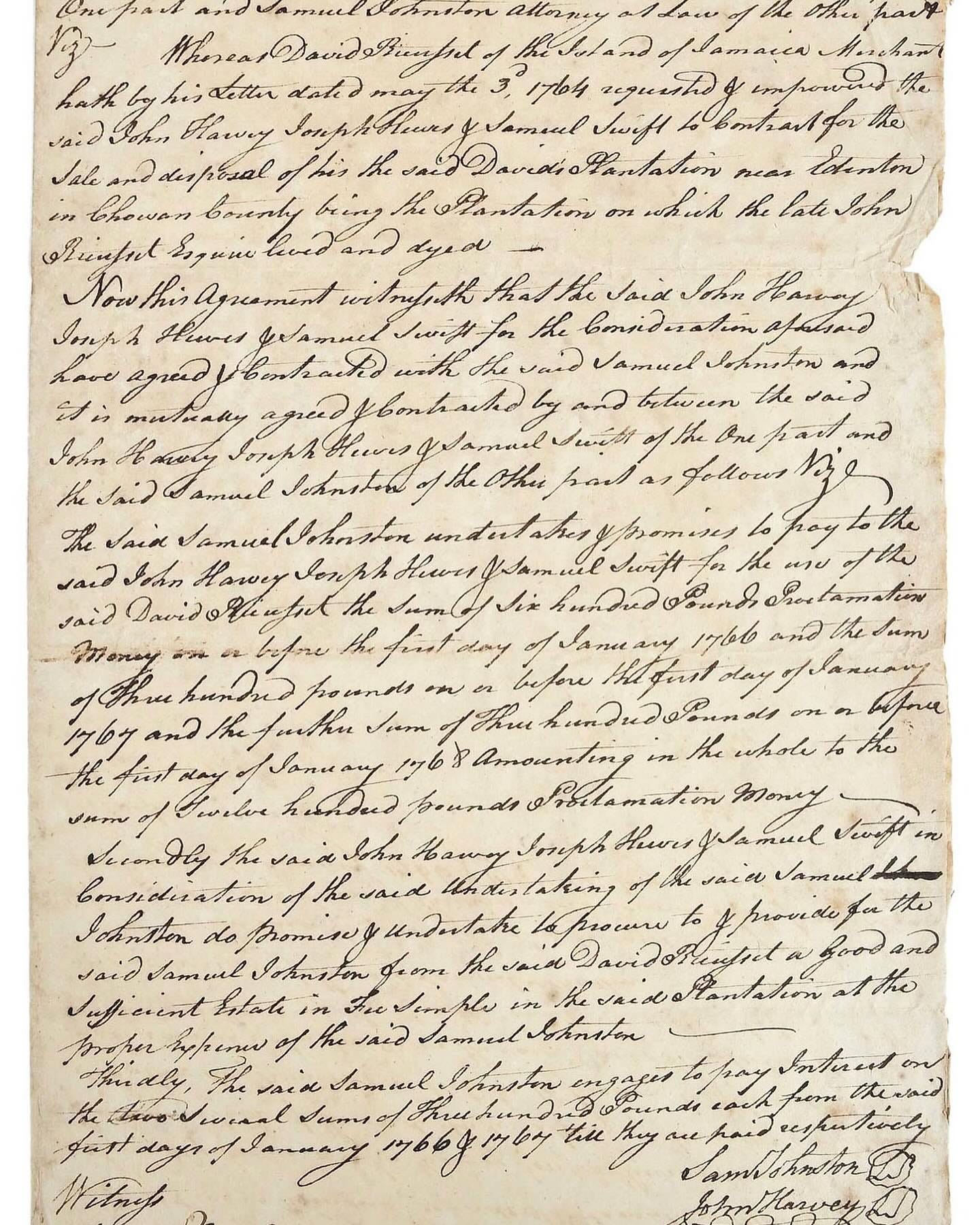

The Constitution notwithstanding, however, quick thinking on behalf of the EVM Foundation and supporters of the efforts at Hayes, combined with the eagle eye of team member and historian Robert Leath, who realized that an auction document billed simply as a contract for the sale of a plantation was actually the original contract for the sale of Hayes to Samuel Johnston, resulted in enough funds raised to not only win this document at auction but also a set of silver spoons, a pair of punched brass valances that were originally in the Hayes dining room, a 19th century Arrowsmith map of Africa, early copies of three very important 19th century speeches, and Samuel Johnston’s 1791 copy of the Constitution and Rules Pamphlet of the St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia, all of which will now be returned home to Hayes.

Meanwhile, a scant few blocks away at Cupola House, a homecoming of another sort was in progress. As mentioned earlier in this post, the sale of much of the original interior woodwork from that house to the Brooklyn Museum in 1918 was the catalyst for the formation of Edenton’s Cupola House Association.

Following the sale, faithful reproductions were installed in the house, which was opened to the public and has been a mainstay of Edenton’s historic attractions ever since. And across the years, hope remained that someday the originals would be reacquired from the museum and returned home where they belonged.

In an exciting turn of events just a few months ago, that hope was realized. The Brooklyn Museum reached an agreement with Cupola House to return the original interiors to their rightful place after having been in exile for 106 years.

As of this writing, the process of removal from the museum, packaging for transport back to North Carolina, and the reinstallation at Cupola House is in full swing. Team members Andrew Ownbey, Wade Rogers, and others from Edenton traveled to New York and connected with renowned architectural historian, Ralph Harvard, and his wife, Clifford, to oversee the transition. The Harvards were involved not only with the removal in Brooklyn, but have agreed – much to the delight of everyone in Edenton – to assist with the homecoming as well.

And there is more. This past weekend marked the 250th anniversary of the Edenton Tea Party, which occurred in 1774 when Edenton resident, Penelope Barker, convinced fifty-one of her women friends to form an alliance to formally protest taxation without representation in America. It was one of the earliest organized political protests by women in the history of our nation. The anniversary celebration, which was sponsored by the Edenton Historical Commission, featured a lecture by Margaret Pritchard, retired Deputy Chief Curator of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, as well as a colonial market, a reception, a parade, and fireworks.

Perhaps you view the confluence of events in Edenton over the past year as mere coincidence, but I take a different view. In my humble opinion, this is the result of more than a century of very hard work and incredible dedication to the cause of preservation by a community whose focus and determination has never wavered.

Stay tuned for future posts, as it is my continuing honor to report on the progress in this remarkable, historic North Carolina town.

Photo of US Constitution auction advertisement via Brunk Auctions. All other photos via EVM Foundation.

I had an interesting conversation on a tour of the area around York, England, last fall. Three of us tourers were alone on the bus waiting for the others. I said I thought it was wonderful how everything was preserved in England. One of the men with me said that yes, thinking of historic preservation was a good thing, but that in England it was too much of a good thing, that people did not think of the future as much as the past and there was little progress whereas in the United States, the thought was for progress and the future. (Another person in England said that we had no history in the United States, which is ridiculous.) There must be, of course, a balance. We must look to the future as well as to the past. And it was not until the Centennial of our founding that we even glanced back. The old buildings, the old silver, the old clothing tie us to our history and join us. I hate to bring in the word "Soul" so soon after mentioning it just a few articles ago. But our physical past helps us have that American soul that binds us together.